The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

Welcome to the “Patten’s reviews” wing of the Anthro Library! Since this is a collection of columns from a dormant (if not dead) furzine called YARF!, a word of explanation might be helpful: In its day, YARF! (aka ‘The Journal of Applied Anthropomorphics’) was perhaps the best-known—and best in quality—of furry zines. Started in 1990 by Jeff Ferris, YARF!’s roster of contributors reads like a Who’s Who of furdom in the last decade of the 20th Century. In any issue, the zine’s readers could expect to enjoy work by the likes of Monika Livingstone, Watts Martin, Ken Pick, and Terrie Smith; furry comic strips such as Mark Stanley’s Freefall… and Fred Patten’s reviews of furry books and comics.

Unfortunately, YARF! has been thoroughly inactive since its 69th issue, which was released in September 2003. We can’t say whether YARF! will ever rise again… but at least we can prevent its reviews from falling into disremembered oblivion. And so, with the active cooperation of Mr. Patten, Anthro is proud to present Mr. Patten’s review columns—including the final one, which would have appeared in the never-printed YARF! #70.

Full disclosure: For each reviewed item, we’ve provided links you can use to check which of four different online booksellers—Amazon.com

, Barnes & Noble

, Alibris

, and Powell’s Bookstore—now has it in stock. Presuming the item in question is available, if you buy it Anthro gets a small percentage of the price.

#29 / Apr 1994 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

| Title: | Magicats II | |

| Editors: | Jack Dann & Gardner Dozois | |

| Publisher: |

Ace Books New York, MY), Dec 1991 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-441-51533-9 | |

|

213 pages, $3,99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

Here are still more fantasy short stories about cats! Yarf! has already reviewed DAW Books’ two Catfantastic anthologies, but Ace Books’ Magicats series is actually older. The first volume was published in June 1984.

These anthologies are similar in that both are devoted to short stories about bizarre cats, or cats in bizarre situations. But there are differences between them. Catfantastic features brand new stories written especially for that series. Magicats consists of reprints—the best SF and fantasy cat tales written over the years. Catfantastic stars domestic pusses, while Magicats is open to felines of all species. Housecats do predominate, but mountain lions, tigers, and jaguars are also present.

There is also a subtle distinction in emphasis. Each of the Catfantastic stories is a short adventure fantasy in which a cat is the lead or pivotal character. Doubtlessly the authors were influenced toward this slant by being asked to write for an anthology featuring cats. Each Magicats story contains a cat, but the cat may be incidental rather than the main focus. These stories were not all written with a cat foremost in the author’s mind. The focus in some is on the message (the horrors of war), or on the human characters (the animal rights movement), or on the genre (comedy or murder mystery). These stories contain cats who may be vividly presented and may be central to the action, but they do not seem to be necessarily cats. They could have been dogs or some other animal just as easily. So Magicats and Catfantastic are not simply duplicates of each other. Each series has a different ‘flavor’ to it.

The dozen stories in Magicats II span the three decades between 1961 and 1991, with the exception of John Collier’s 1940 A Word to the Wise. They are all excellent reading, although only three of the twelve really have anthromorphized cats: the Collier anecdote, Fritz Leiber’s Kreativity for Kats, and Pamela Sargent’s The Mountain Cage. Two are about human were-felines: Lucius Shepard’s The Jaguar Hunter and Avram Davidson’s Duke Pasquale’s Ring. Three are fantasies featuring ordinary cats: Isaac Asimov’s I Love Little Pussy, Ward Moore’s The Boy Who Spoke Cat, and Tanith Lee’s Bright Burning Tiger. (Well, Lee’s fiery tiger is hardly ordinary, but it is not anthropomorphic.) The last four stories not only feature normal felines, they are not even fantasies. Michael Bishop’s Life Regarded as a Jigsaw Puzzle of Highly Lustrous Cats is surrealistic stream-of-consciousness of a psychotic who is obsessed with cats; Ursula K. LeGuin’s May’s Lion is a sociological essay showing how women from two different cultures would perceive a cougar; and Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Sin of Madame Phloi and R. V. Branham’s The Color of Grass, the Color of Blood depict life (and death) in modern American homes from a housecat’s point of view.

From the specific aspect of anthropomorphism, the Catfantastic series will be of more interest to readers of Yarf! than Magicats. But if you like good writing, fantasy, and cats—anthropomorphized or not—then you will have to read both series. ![]()

|

||

| Title: | Turning Point | |

| Author: | Lisanne Norman | |

| Map: | Michael Gilbert | |

| Publisher: |

DAW Books (New York, NY), Dec 1993 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-88677-575-2 | |

|

267 pages, $3.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

’Morph fandom has a reputation that is practically synonymous with furry eroticism. Well, it’s not just ‘us’ any more. Here is an inter-species romantic space opera that lets it all hang out and is proud of it. A human woman meets a felinoid alien—a handsome, studly, furry hunk of a cat-man—and:

From the first she’d felt drawn to him in a strange fascinating way. Then she’d felt it change to something more. Was this truly what she wanted? She knew that two worlds not two people stood beside the tree. Could they, would they… dare… make that bridge?

When she spoke, her voice was a barely audible whisper.

“Then may your gods pity me, too, because I seem to have no choice either.”

Kusac froze. “What are you saying?”

“That we aren’t very different. That I find myself as drawn and bound to you as you are to me.”

“Then we will have to face the future together?” he asked, hardly daring to breathe.

“Together,” she replied, looking up at him and seeing again the person that he was as well as the Alien form he wore.

Carrie buried her face in the fur on his chest, deeply breathing in his musky scent. She clutched at his back, running her hands through the soft pelt, aware of the strength of the muscles underneath. (pg. 138, abridged)

Carrie Hamilton is a repressed young woman on a male-dominated world. Not only does the colony planet Keiss have a strongly patriarchal society, but it has recently been conquered by brutally militaristic aliens, the Valtegans. Keiss’ menfolk are fighting a guerrilla war to regain their freedom, but Carrie is considered too delicate to help. She has an uncontrollable telepathic talent that makes her overly susceptible to the pain and stress felt by others, a liability in combat situations. Her father and brother are arranging to marry her to the town’s richest and most arrogant lout, smugly sure that they are acting in her best interests and that her opinions are not worth listening to.

The first time that Carrie stands up to them is when she finds an injured cougarlike forest cat, and insists on nursing it. Only Kusac isn’t a wild animal. He’s a member of another alien race that’s also at war with the Valtegans. His spaceship was shot down on a reconnaissance mission, and he was too badly injured to keep up with his felinoid shipmates as they escaped into the forest. Kusac is the Sholan team’s telepath, so he quickly senses how good-hearted Carrie is.

Turning Point is skillfully composed as a light adventure space opera, but it’s not hard to see all the wish-fulfillment clichés beneath the surface action. Everyone else is frightened of the fierce animal Kusac appears to be; only Carrie senses his inner nobility. Kusac uses his telepathic powers to train Carrie to control her own gift, helping her to grow from a confused girl into a strong woman. As she nurses him back to health, he gradually turns from a wild animal who is her loyal protector into (once he drops his telepathic disguise) a handsomely humanoid cat-man; the beast becomes the Beast to her Beauty. He next rescues her from her impending forced marriage, as they use their combined telepathy to find and join the other Sholans. When one of the more paranoid cat-men attacks Carrie, Kusac fights a spitting, clawing animal battle to protect her. Carrie is the only one who can bring the mutually suspicious Sholans and the human guerrillas together to fight the Valtegans as allies. And when the macho guerrillas want to send her back home to safety, it’s Kusac who demands they let her show that she can fight just as well as a man.

The romantic theme runs overtly throughout the action. True love becomes reinforced by their telepathic link into an unbreakable bond. Both the Sholans and the humans have trouble accepting the inter-species romance, but they are proud to openly display their affection. Let it serve as a model for future human-Sholan friendly relations. The novel ends abruptly, with Carrie’s family convinced to welcome Kusac as a son-in-law, and the two lovers about to journey to Shola to break the news to his family. There is obviously room for a sequel, to tell what happens to Carrie as the only human on a planet of cat people. Is one coming? ![]()

2007 editor’s note: In fact, there was room for several sequels—Turning Point turned out to be the first novel in Norman’s seven-books-and-counting Sholan Alliance series. They are, in order:

Turning Point (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Fortune’s Wheel (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Fire Margins (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Razor’s Edge (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Dark Nadir (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Stronghold Rising (Am/ BN / Al / Pw)

Between Darkness and Light (Am/ BN / Al / Pw).

#30 / May 1994 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

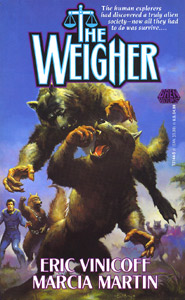

| Title: | The Weigher | |

| Authors: | Eric Vinicoff & Marcia Martin | |

| Publisher: |

Baen Books (Riverdale, NY), Nov 1992 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-671-72144-5 | |

|

313 pages, $4.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

This SF novel does a fine job of establishing an alien culture that seemingly shouldn’t exist. The novel is narrated by Slasher, a razor-fanged, bloodthirsty carnivore on a distant planet that is discovered by Ralph and Pam Ayers, a husband-wife pair of human explorers. The Ayers do not take a major role until about ninety pages into the story; the opening is devoted entirely to establishing Slasher’s lively, vivid daily life.

Groundplant was a springy, rust-colored blur under my driving paws. I was running at my best long-distance pace, not quite as fast as when I was in my prime, but not dallying either. The wind whistled through the pounding drum-rhythm, while it ruffled my fur and cooled my burning muscles. I sucked in quick, deep lungsful of it, enjoying the rich variety of forest scents. […] I caught up with a coal-laden wagon rattling toward town. A tagnami was loping beside the pair of runlegs, herding them with snarls and nips. Runlegs made poor hunting, tasted terrible, and were only slightly smarter than the boulders they resembled.

“Get those abominations out of my way!” I yelled irritably.

The tagnami glanced over his shoulder, saw me, and yelped, “Yes, Ma’am!” Snarling at the runlegs, he drove them over to the right side of the trail. I hurried past the wagon. […] The wrought-iron gate was open. I stood up on my hindlegs and walked under the stone arch. The first thing I noticed upon entering Coalgathering was, as usual, the reek. Even after a night of airing out, the town-smells set my fangs to aching. Trying to ignore them, I headed for the middle of town. (pgs. 1-3, abridged)

Slasher is Coalgathering’s town Weigher, the closest thing this society has to a civic official. She acts as an arbitrator in any disputes whose participants are willing to settle them peacefully rather than take them to the town’s challenge lawn, where disagreements are fought until one litigant is dead. Only Weighers who are strong enough to enforce their rulings are respected, so Slasher must maintain her reputation as the potentially deadliest fighter in town as well as its wisest balancer of fairness. Since she is getting past her physical prime, she is resigned that it will probably be only another few seasons before she is fatally replaced by a younger and more agile challenger.

All this is changed when two strange monsters float down from the sky and introduce themselves as people from another world who want to study this one. Partly because they are immediately challenged by an enemy of Slasher’s, she keeps them from being instantly killed. She also realizes that they may be able to offer new viewpoints that will help with some problems that she has been having with some of Coalgathering’s more troublesome inhabitants.

By this point, the reader is probably wondering how such ferocious, vicious animals could ever coexist long enough to form any society. This is practically the first thing that Ralph and Pam Ayers start asking:

“Our working hypothesis is that you evolved intelligence as a defense against a danger greater than starvation or hostile predators.”

My back fur rose instinctively. “What danger?” I asked sharply.

“Yourselves.”

My fur subsided, but I felt another confusion-generated headache coming on. “I don’t understand.”

“With your territorial instinct and year-round breeding, there must always have been tremendous population pressure and competition for the best land. Smarter people fought better and figured out ways to avoid more fights. They tended to be the survivors and the breeders.” (pgs. 115-116)

Unfortunately for Slasher’s people, they were lone predators before they were social animals. The instincts for communal living and cooperation are comparatively weak. The evolution into townships with populations in the low hundreds has already reached about as far as it can go before people start growing murderously irritable through overcrowding and too many differences of opinion. Slasher can intellectually understand that her world has only another few generations before it suicidally self-destructs. But she still embodies her species’ instincts. Her attempts to arrogantly force Coalgathering to adopt improvements based upon the humans’ knowledge sparks a conservative rebellion that forces her and the Ayers into a humiliating exile. Humiliating to her, that is; the two humans are fascinated by their involuntary trek across this world, looking for a new community to settle into. And Slasher must settle the turmoil between her individualistic ego and her understanding of the need to promote cooperation rather than dominance, for her world’s good as well as her own.

Ken Kelly’s cover painting for The Weigher shows Slasher and her people as a cross between shaggy large wolves and grizzly bears. Some of the situations imply that they may be more lean and lithe than this, and their tails are definitely prehensile enough to be significant aids in a fight:

She leaped over me, a flashy but effective move. Her foreclaws raked at my back. But I wasn’t there; I had dropped to my belly, rolled and crouched. I tried to hook one of her hindlegs with my tail, but missed. (pg. 297)

Since The Weigher is told from Slasher’s viewpoint, the reader is in the midst of the anthropomorphic action at all times. Vinicoff & Martin develop an elaborate and fascinatingly appealing society, considering how bloody it is. There are scenes depicting these carnivores’ feral courtship, family life, education, commerce, shipping, and even religion. ![]()

#31 / Jul 1994 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

| Title: | Animal Brigade 3000 | |

| Editors: | Martin Harry Greenberg and Charles Waugh | |

| Publisher: |

Ace Books (New York, NY), Feb 1994 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-441-00014-2 | |

|

276 pages, $4.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

MAN AND BEAST—UNITED IN BATTLE […] Harnessing the combined force of instinct and intelligence, evolution and engineering, these interspecies teams join in combat—and in the universal fight for survival… (blurb)

This anthology features seven stories about teams of human and animal partners in dramatic situations on interstellar worlds. The creatures range from ’morphs to intelligent aliens to well-trained domesticated beasts. Four of the stories are reprints; three are written especially for this anthology.

Unfortunately, this concept works better in theory than it does in actuality. For starters, over 40% of the book is filled with the 113-page Dragonrider, by Anne McCaffrey. This was the second Pern story in Analog SF, the sequel to her Weyr Search. The two together comprise Dragonflight (1968), the first novel in McCaffrey’s classic series about the human Dragonriders and their intelligent native dragon partners who protect the world of Pern from the deadly Thread-like spores of a neighboring planet. That novel is certainly worth reading, but in its entirety. Why read Part 3 and Part 4 without Parts 1 and 2? And if you don’t read Dragonrider, almost half of Animal Brigade 3000 is wasted.

On the Tip of a Cat’s Tongue, by Karen Haber, introduces private detective Willem Seaton to a rich client who talks through her cat.

Belatedly Seaton remembered the story: a cruiser docking error. Three passengers killed, five badly hurt. One—Kembali Val, level-two curator—had survived. But her throat, her voice, was gone. The doctors had fitted her with prostheses and a cyber-link to the animal—and new voice—of her choice.

“My situation takes everyone by surprise at first,” the cat continued. “My voice’s name is Sebastian. He does not enjoy being petted by strangers. Please sit down.” (p. 116)

The imagery is striking of the detective who reports to a stately woman whose voice comes from her pet cat as it wanders through her office. And the mystery is a clever one. But the cat seems to be more of an unusual prop than a character.

Exploration Team, by Murray Leinster (1956), puts two humans, three giant Kodiak bears and a cub, and a bald eagle on a hell-world where every native life form is ferociously deadly to mankind. The eagle is merely well-trained, while the bears (Sitka Pete, Sourdough Charley, Faro Nell, and her cub Nugget) are giant, bioengineered mutations. “There was need, on my home planet,” the frontiersman Huygens explains to Colonial Survey officer Roane, “for an animal who could fight like a fiend, live off the land, carry a pack and get along with men at least as well as dogs do. […] the bears want to get along with men. They’re emotionally dependent upon us! Like dogs.” (p. 156). There is constant drama as the humans and bears trek through the jungle to the rescue of colonists who had relied on robots to keep them safe from the hellish sphexes, the night-walkers, and other monsters. There’s also some humor as the slightly stuffy Roane learns how to get along with the 12-foot-tall, two-ton, slobberingly friendly Teddy bears. The story was written for an earlier generation, however. Today’s readers may not be totally receptive to the clever concept of settling a planet by killing off all the native animals and replacing them with nice, safe mammals bred to love humans.

All the Angles, by Jack Nimersheim, is the first story here with a real ’morph character. In fact, it’s narrated by Thom Cat, the feline partner of Jerry Jones, a professional team of human and enhanced animal. ‘Professional’ what? Thom spends so much time arrogantly boasting about how clever he is that the little details never get described. Thom’s story is about how he and Jonesy hired out as mercenary secret agents to the Deimos government which was losing a rebellion against Mars, and he personally won the war for little Deimos. In one scene, Thom is briefly mistaken for a normal cat (until he starts mouthing off), so presumably he is not very physically different from one. But in another scene, “Withdrawing the laser knife from my neck pouch, I cut through the fine mesh in less time than it takes to tell you about it;” implying that he has hands instead of paws. The story would be more enjoyable if it had less back-patting dialogue and more details about the characters and action.

The Undecided, by Eric Frank Russell, is the oldest story (1949). A Terran spaceship crashes on a distant planet. The crew of eight must defend themselves from the hostile local military until they can repair their ship and blast off. Although the Terrans talk telepathically among themselves, the story is told mostly from the point of view of the aliens. Sector Marshal Bvandt slurged in caterpillarish manner across the floor and vibrated his extensibles and closed two of the eight eyes around his serrated crown and did all the other things necessary to demonstrate an appropriate mixture of joy, satisfaction and triumph. (p. 193). Bvandt and his aides grow increasingly frustrated as their attempts to capture or destroy the mystery spaceship are stymied by its unknown inhabitants, who each seem to be of a completely different species. The sluglike locals wonder (as the reader is obviously supposed to) whether its crew is composed of amorphous shapeshifters, or maybe the master races of several different worlds of a space empire. But since this story is in Animal Brigade 3000, the reader will guess from the beginning that the Terrans consist of one human and several different intelligent animals (dog, cheetah, owl, etc.) who have evolved into a society of mutual equality. (Yeah, but it’s still the human who’s the captain.)

Schurman’s Trek, by Roland J. Green, is set on a planet where human scientists are helping to establish a colony of bioengineered elephant ’morphs, the Hathi, during an interstellar war. When the planet is attacked by the enemy, human Roberta Schurman and Hathi Clan-Mother Drina have to lead the nervous elephant people on a long, dangerous trek to safety. This is the best story in the anthology for depicting a ’morph culture that mixes the instincts and attributes of its base species with human intelligence.

Harry Harrison’s 1967 The Man from P.I.G. was written at the height of the James Bond/Man from U.N.C.L.E. craze, and is a humorous s-f variant on that theme. A newly-colonized planet appears to be haunted; its harried Governor calls the Patrol for a top-notch Secret Agent to save them; and all that he gets is an amiable farmboy with a herd of squealing pigs! But this is Bron Wurber, the Man from P.I.G. (Porcine Interstellar Guard). His boars and sows are better-trained than the best attack dogs. Harrison plainly studied up on swine, and he works a lot of data about the different breeds and their abilities and capabilities into this adventure, as Bron’s detective work brings him and his herd under attack by the evil alien empire’s saboteurs and their criminal human hirelings. There are no ’morphs here, though; only domesticated animals.

So Animal Brigade 3000 is a mixed bag. There are only three stories featuring real ’morphs, and one of those is more annoying than enjoyable. Three other stories are worth reading, although they are about trained animals rather than ’morphs. And the longest in the book, Dragonrider, cannot be recommended as long as McCaffrey’s Dragonflight is easily available instead. ![]()

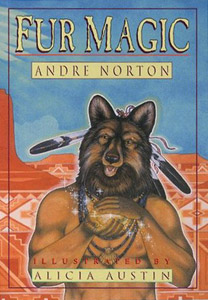

Cover of the deluxe edition |

||

| Title: | Fur Magic | |

| Author: | Andre Norton | |

| Illustrator: | Alicia Austin | |

| Publisher: |

Donald M. Grant, Publisher (Hampton Falls, NH), May 1993 |

|

| ISBN: | 1-880418-20-7 | |

|

173 pages, $18.00 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

|

|

||

|

Deluxe edition |

||

| ISBN: | 1-880418-19-3 | |

| 173 pages, $65.00 | ||

| Availability: | Am |

|

This juvenile fantasy featuring Native American themes was originally published in 1968. Norton was a Guest-of-Honor at the 1992 World Science Fiction Convention in Orlando, FL, and this lavishly illustrated edition of Fur Magic was intended to commemorate that occasion. Unfortunately, production difficulties postponed it for so long that it was not published until the middle of the following year. But it is available now, and the delays have not affected the quality of the book.

Cory Alder is an urban child spending a Summer vacation at his dad’s Army buddy’s ranch in Idaho. But what was supposed to be a treat has turned into a severe emotional trauma. The shy boy has discovered that he is terrified of real horses and of the great outdoors.

Cory’s ‘Uncle Jasper’ and their ranch hands are Nez Perce’ Indians. From their conversation, Cory picks up the native myths of the beginning of time, when the Old People, the animals, lived in tribes and conducted their affairs as the Indians themselves later did. Then the Changer (Coyote to the Nez Perce’; Raven or other animals to different tribes) created humans, and the world turned upside down. According to the legend, the Great Spirit exiled the Changer for his meddling. He has been trying to get back and correct his mistake ever since, by using his trickery to make mankind destroy itself so the animals will rule the world once again. Uncle Jasper comments sardonically that, considering what the world news says about the way humanity is headed, that’s not so hard to believe.

As Cory wanders about the ranch, he stumbles over the hidden medicine bundle of Black Elk, an ancient medicine man who follows the old ways. The shaman insists that Cory must purify the bag by holding it in a stream of strangely-scented smoke. The smoke makes Cory dizzy; when he recovers, he is in the body of Yellow Shell, a beaver warrior in the days of the Old Ones.

Most of Fur Magic is the story of Cory as Yellow Shell of the beaver tribe, who was on a scouting mission against war parties of the vicious mink tribe. Cory has Yellow Shell’s memories but his own mind. The frightened human child is no match at first for the seasoned animal warriors. He is led by an otter brave to the otter tribe’s village, where he learns that the old ways are beginning to change. The minks have grown bolder and are now in alliance with the crows, who are spies of the Changer. The Changer is the enemy of the Old People, for they know that in his arrogance he is about to make a new animal (man) who will enslave all the other Peoples. The otters’ shaman recognizes that Cory/Yellow Shell is two spirits within one body, and this is a wrongness which only the Changer himself can alter. The medicine otter lets Cory join two emissaries who are being sent with a peace pipe to the tribe of Eagle, where he may find advice on how the Changer can be persuaded to aid him. Thus the boy begins a quest to return to his own body and world, learning self-reliance and courage in the process.

Fur Magic is more successful as a broad panorama of this mythic America inhabited by the animal tribes, than as an adventure story. Cory is the only major character; all others are met only in passing, and are gone within two or three pages. There is practically no dialogue. Yellow Shell was on a lone scouting mission when Cory entered his body; no other beavers are encountered, and Yellow Shell does not know the languages of any of the other animals whom they meet—they communicate only briefly through sign language. There are several hints that Cory is being invisibly guided and protected during his quest (But time was important. He could not be sure how he knew that, only that it was so.), which removes any real dramatic suspense. What is left is the spectacle; the landscape of the pure American wilderness, inhabited by animals dressed as Indians and following indigenous customs.

This is why the novel excels through Alicia Austin’s artwork. Austin is an award-winning fantasy artist who specializes in paintings and allied graphics depicting animals wearing the clothing of their lands’ native peoples—North America, Africa, the Arctic Circle, etc. This is exactly what Norton has described in Fur Magic. The characters are not anthropomorphized to the usual funny-animal extent; they are large but otherwise normal animals who are wearing little more than ceremonial body paint, and carrying a buckskin or turtleshell pouch and a spear or two. Austin shows these in ten full-color plates—one for each chapter—and forty black-&-white illustrations; practically one for every other double-page spread. The book, like all of the Donald M. Grant fine editions, is printed on top-quality paper and has sewn binding within sturdy blue cloth-covered boards. This is a novel that you can be proud to display on your bookshelf. ![]()

|

|