The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

Welcome to the “Patten’s reviews” wing of the Anthro Library! Since this is a collection of columns from a dormant (if not dead) furzine called YARF!, a word of explanation might be helpful: In its day, YARF! (aka ‘The Journal of Applied Anthropomorphics’) was perhaps the best-known—and best in quality—of furry zines. Started in 1990 by Jeff Ferris, YARF!’s roster of contributors reads like a Who’s Who of furdom in the last decade of the 20th Century. In any issue, the zine’s readers could expect to enjoy work by the likes of Monika Livingstone, Watts Martin, Ken Pick, and Terrie Smith; furry comic strips such as Mark Stanley’s Freefall… and Fred Patten’s reviews of furry books and comics.

Unfortunately, YARF! has been thoroughly inactive since its 69th issue, which was released in September 2003. We can’t say whether YARF! will ever rise again… but at least we can prevent its reviews from falling into disremembered oblivion. And so, with the active cooperation of Mr. Patten, Anthro is proud to present Mr. Patten’s review columns—including the final one, which would have appeared in the never-printed YARF! #70.

Full disclosure: For each reviewed item, we’ve provided links you can use to check which of four different online booksellers—Amazon.com

, Barnes & Noble

, Alibris

, and Powell’s Bookstore—now has it in stock. Presuming the item in question is available, if you buy it Anthro gets a small percentage of the price.

#42 / Jun 1996 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

| Title: | House of Tribes | |

| Author: | Garry Kilworth | |

| Illustrator: | Paul Robinson | |

| Publisher: |

Bantam Press (London), Nov 1995 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-593-03376-0 | |

|

[xiii +] 430 pages, £12.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

Kilworth has established a reputation as an author of ‘realistic’ talking-animal novels in the vein of Watership Down, with Hunter’s Moon: a Story of Foxes; Midnight’s Sun: a Story of Wolves; and Frost Dancers: a Story of Hares. House of Tribes is a bit different—in fact, it is accurately blurbed as ‘An epic animal fantasy in the tradition of Duncton Wood.’ The animals are superficially like Watership Down’s rabbits, but a bit too clever and well-organized to pass as ‘realistic’.

Pedlar is a young yellow-necked mouse born into a Hedgerow community of British wildlife. They are three fields away from the House, a fabulous paradise too good to be believable:

Wandering rodents had entertained the hedges and ditches with tales about the House. It was a place where mice lived in comfort, they said, warm all the year round. It was a place where food was in plenty, whatever the season, whatever the weather. It was a place where a variety of different species of mice made nests above ground, yet still remained out of the rain, out of the wind, out of reach of the fox and weasel, the stoat and hawk. (pg. 3)

But Pedlar begins to have a Dream urging him to go to the House, for his destiny is to play a part in a great event which will befall the mice there. Dreams are believed to be messages sent by the departed ancestors and guardians of all mice, so Pedlar is morally pressured to uproot his life and venture to the House despite his doubts.

Pedlar becomes so involved in the complex society within the old country mansion that he (and the reader) tend to forget about the plot. The House is no happy playground, although it is more full of mice than it should be. Readers will recognize what the mice do not; the House’s nudnik (human) inhabitants are old and probably senile, and are mostly unaware of the horde of vermin robbing their pantries and chewing up the books in the vast Library. There is a sadistic child among them, but his death traps are usually easily avoided. (Mice who do fall prey are fed to his psychotic, cannibalistic pet white mouse.)

The House has become overpopulated with mice, who have separated into warring tribes; one for practically every room. The kitchen mice, who control the coveted never-empty larder, are the Savage Tribe, marked by Viking names like Jarl Forkwhiskers, Gytha, and Tostig, and led by the appropriately brutal and bloody Gorm-the-old. The library mice, the Bookeaters such as Owain, Cadwallon, Rhodri, and Gruffydd Greentooth, are literati and mystics, led by Frych-the-freckled who is into witchcraft and black magic. The attic-dwelling Invisibles are aloof cynics who give each other sarcastic names like Whispersoft (he invariably bellows), Nonsensical (the most practical in their tribe), and Ferocious (a coward). The cellar-dwelling Stinkhorns have vulgar names like Phart and Flegm, and you don’t want to know their personal habits. Pedlar gets so involved with these colorful personalities (and others), and their intra- and intertribal feuds, that it comes as a shock when the plot resumes more than a hundred pages later, and we are reminded that Pedlar is there for a purpose.

Although the divine larder is never empty, it never has enough for all the mice at the same time. The main reason is that the mice are forced to wait for quiet after dark, while the giant nudniks can come into the kitchen and eat as much as they want whenever they want. Gorm-the-old decides to call a House-wide crusade to drive out the nudniks, so the larder will be all theirs. Astrid the high priestess prophecies disaster and a great famine if they are successful, but Gorm (who envisions all mousedom united under his leadership) bulls ahead anyway. Pedlar, not sure whether he should participate in the Great Nudnik Drive or oppose it, is swept up in the hysterical frenzy which will change all of their lives forever.

Kilworth is talented at establishing his almost-identical mice with sharply individual personalities and characteristics. The story unfolds with drama and wit:

Gorm-the-old was a legend in his own time and the story of his rise to power was told to every new infant of the Savage Tribe, whether they wanted to hear it or not. Now he was placing that legend on the line. (pg. 125)

There is a mood of both fatality and of challenge. It gradually becomes obvious that the lives of the mice are to some extent preordained, but their fates can be changed if strong individuals recognize the crisis points and act upon them. Unfortunately, the Fates never speak clearly. Pedlar must gamble as to whether he has been sent to support Gorm in his daring crusade, or to save the mice from Gorm’s madness. To the reader, who will have a more realistic idea of the results of mice attacking humans, the question is more as to whether Pedlar himself can survive, or help any of his friends among the House mice to survive. The results may surprise you. ![]()

|

||

| Title: | Summerhill Hounds (First Quest™ Books) | |

| Author: | J. Robert King | |

| Illustrator: | Terry Dykstra | |

| Publisher: |

TSR, Inc. (Lake Geneva, WI), Nov 1995 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-7869-0196-9 | |

|

250 pages, $3.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

The First Quest™ Books are a series of ‘Young Readers Adventures’ set in the Endless Quest™ gaming world. Although it is a straightforward novel, its literary style and quality are closer to those Choose Your Own Adventure paperbacks. It is a very simplistic adventure in a very stereotypical fantasy setting. But it is certainly anthropomorphic. To quote the back-cover blurb:

Castle Dunkirk might have been musty and moldy, but for the Summerhill Hounds, it was home sweet home. Sheepdogs, collies, mastiffs, cockers, terriers, bloodhounds—a veritable mess of domesticated dogs—lived and worked around the massive fortress. But that was before the orc attack. Now, all is gone … castle … soldier friends … days of idyll. The dogs must band together to pursue the piggish warriors that are marching their men into captivity. Their decision sets them on an adventure in which—battling odds and strange creatures—they must dig deep within themselves, discover bravery and fantastical powers, and learn to live wild and free.

Keep in mind that this is intended for ‘Young Readers’. Otherwise it is too easy to criticize its lack of sophistication. Fantasy-adventure role-playing settings are, by definition, not realistic, but they need to be pseudo-realistic enough to sustain a modicum of believability and suspense. The stereotype of Summerhill Hounds is closer to that of generic Disney animation, especially the funny-animal Robin Hood movie—the one where the Sheriff of Nottingham has Pat Buttram’s hillbilly accent. Here it’s the ‘old codger’ bloodhound, Lank Leonard, whose accent and manners of “southern gentility” (pg. 129) make him sound like the twin of Trusty in Lady and the Tramp—not exactly what one would expect in a setting of early Norman castles with orcs and the Celtic Seelie Court just the other side of the drawbridge.

We all know that medieval courts included packs of hunting dogs. But would you believe a pack that resembles the cast of a dog show? There’s Mongy the terrier; Reedel the English sheepdog (the furballs with hair covering their eyes—just picture one of those in a manor lord’s deer hunt); Merry the collie; Dea the golden retriever; the aforementioned Lank Leonard; Goldie the cocker spaniel; Gray the deerhound; Sheba the part-wolf deerhound; and Slav the black mastiff. Slav is actually an enchanted fire-breathing mastiff, which is a nice touch of originality; otherwise the crew resembles the multibreed stray-dog casts of Lady and the Tramp or Oliver & Company more than what one expects in a sword-&-sorcery landscape. And, as soon as the bloody capture of the castle is finished, the orcs suddenly start bumbling around more like the buffoonish ogres from Disney-TV’s The Gummi Bears than the serious menaces of Middle Earth.

There is also the Watership Down-based stereotype of ‘realistic’ animals who have their own language, folklore, and religion. But King’s dog-legends unfortunately lack the word-magic of Adams, Kilworth, Horwood, et al. Two ancestral wolf packs are the Griooowas and the Uuffuffs. The legend of the Silver Dog and the Seelie Hound isn’t bad, but it loses a lot when his First Dogs have names as pedestrian as Humphrey, Ivy, and Kelly.

One coincidentally identical conceit both here and in Kilworth’s House of Tribes is the least convincing aspect of both novels: That the dogs/mice believe themselves to be intelligent and sophisticated, but that the humans whose buildings they live in are only dumb animals—their pets, here, and unpleasant vermin (like giant cockroaches) in House of Tribes. It’s amusing to observe these animals considering themselves to be so superior, but not really believable that characters smart enough to realize what intelligence and self-awareness are would not recognize the same traits in the humans whom they can see talking among themselves and manipulating utensils.

What happens to the loyal dogs (plus a supercilious cat named Gato) cast loose in a countryside of fierce wolves, brutal orcs, and a magical Celtic faery realm is at least unexpected. And it’s a quick and relatively inexpensive read. If Disney intends to make any more movies along the lines of The Aristocats or The Black Cauldron, they might keep this novel in mind. ![]()

#43 / Aug 1996 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

| Title: | Mink! | |

| Author: | Peter Chippindale | |

| Illustrator: | Matthew McClements (map) | |

| Publisher: |

Simon & Schuster Ltd. (London), Sep 1995 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-671-71916-5 | |

|

566 pages, £9.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

Here is another new “Animal Farm for the ’90s”, according to the cover blurb. Well, it does feature talking animals, and it is written for adults. But it seems closer to Watership Down than to Animal Farm. There is certainly satire in it, but it remains subordinate to a complex and taut drama of politics and survival. Mink! feels more like a talking-animal version of such 1950s and ’60s political thrillers as Forbidden Area or Seven Days in May.

The first half of the 566-page novel consists of two parallel stories, told in alternating chapters. The first begins with the birth of Mega, a mink, into a dirty, overcrowded British countryside fur farm. The colony is dominated by an aristocracy of conservative Elder mink who rule as high priests. As Mega grows, he is smart enough to see that the creed of peace and brotherhood is more for the Elders’ own good than that of the restless, high-strung common mink. They have the choicest benefits of their cramped world without having to fight for them, as mink instinctually do.

In the parallel story, the animals of the nearby Old Wood are being nagged by a group of Concerned Woodland Guardians, led by the rabbits, into forming a cross-species ‘Woodland Code’ and ‘Bill of Creatures’ Rights’. But even its most ardent advocate, Burdock, must admit that they are getting nowhere. The animals that do accept the concept of animal rights just splinter into factions—Frogs for Freedom, Worms’ Lib, and the like—which spend all their time making endless speeches and referring proposals to Committees. Also, one key group is not represented; the predators. Burdock’s solution is to persuade one of the more influential of the predators, Owl, to become involved; as much for his shock value as anything else. Also, Owl is the only predator with the intellectual curiosity to be interested in the social affairs of the ‘veggies’, as his fellow predators disparagingly call them. So in the first half of the novel, the story switches back and forth as Mega plots the takeover of the mink community from the decadent Elders, then must figure out how to free all the mink from the human cages; and as Burdock wheedles and cajoles his Congress of herbivores towards accomplishing something, while Owl watches with a combination of boredom and dilettante fascination.

When the escaped mink arrive in the Old Wood, the two stories merge with the impact of When Worlds Collide. New questions and plot twists arise with increasingly dizzying rapidity. Should the resident predators consider the voracious mink as ‘brothers’, or join forces with the herbivores to oust the invaders to protect their own food sources? Or should it be every animal for itself? What can herbivores do in defense against such overenthusiastic murderers? What ‘rights’ are realistic when a carnivore has to kill its neighbors to keep from starving to death, whether it would prefer to be a ‘good guy’ or not? Mega is convincingly portrayed as simultaneously a sadistic, kill-crazy slaughterer, and as an idealist who is trying to create a paradise for all mink—and who grows increasingly frustrated with such realities as that the mink may overeat the Old Wood into their own starvation unless they curb their appetites. (Since Mega had promised the mink unlimited feasting to gain their support, this development poses political problems for him, as well.) Owl is convincingly portrayed as realizing that he must turn himself from a detached intellectual into an involved activist; but he can see so many variables resulting from each possible decision that he agonizes over the right action to take. The story keeps springing clever surprises on both the characters and the reader.

The basic plot is an adventure drama and a political thriller strong enough to support plenty of satire, both light-hearted and cynical. British readers are supposed to recognize specific caricatures of prominent public figures of the Thatcher and Major eras among the cast. American readers will get enough humor just out of the clear stereotypes of the Politically Correct, the Do-Gooders, the Devoted Followers who are ready to obey any order, the Manupulators, the Marketing Strategists, the Feminists, and others. The major cast is much more fully developed as realistic individuals than are the famous characters of Animal Farm. Chippindale’s writing is always witty; sometimes obvious, as in the minks’ own version of the British anthem (“Rule Minkmania; Minkmania rules the wood; Creatures ever, ever, ever; Shall be food!”), and sometimes very subtle.

Mink! is extremely highly recommended. It is good enough to be worth the trouble and expense of ordering your own copy from Britain, if no American edition of it comes along soon. ![]()

|

||

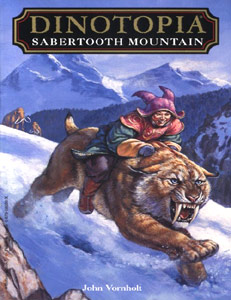

| Title: | Dinotopia: Sabertooth Mountain | |

| Author: | John Vornholt | |

| Illustrator: | ? (map) | |

| Publisher: |

Random House/Bullseye Books (New York, NY), Jun 1996 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-679-88095-X | |

|

133 pages, $3.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

I just reviewed Bullseye Books’ first four Dinotopia juvenile novels in Yarf! #41. I didn’t expect to return to them so soon, but I can’t resist ranting about how this latest virtually destroys the concept of Dinotopia.

James Gurney’s premise of a large island where humans and intelligent dinosaurs share a harmonious civilization has always been a fragile fantasy. It is good for art books full of beautifully intricate paintings of men and dinosaurs associating together in friendship and equality. Unfortunately, this is the opposite of the requirements of fiction. Novels need drama and conflict. The contradictions among the adventures in Bullseye’s first four Dinotopia novels already strained the suspension of disbelief needed to accept this human-dinosaur brotherhood.

With Dinotopia: Sabertooth Mountain, it all falls apart. The dinosaurs have become wooly mammoths, dire wolves, giant sloths, cave bears, and all of the other spectacular vanished mammals. The way that these species live in harmony is that, whenever a herbivore or omnivore is about to die of old age, it joins a Death Caravan of elderly philanthropists who totter off to one of the carnivore communities to offer themselves as a meal; so the friendly carnivores are not forced to reluctantly prey upon their neighbors.

13-year-old Cai, a human boy, is accidentally cast away among the sabertooths who live in a valley at the foot of Sabertooth Mountain. There is only one pass into their valley, and a winter avalanche has blocked it off; so no dying volunteers can get in to feed the big cats—who are getting awfully hungry. Redstripe, the leader of the sabertooth pride, wants them to show their will-power and wait until the pass can be cleared. Neckbiter, Redstripe’s rival who is a sabertooth über alles demagogue, wants to leave the valley through a series of dangerous underground passages through the mountain, and start feasting on all the animals of Dinotopia—starting with Cai. Cai and Redstripe are forced to become allies, escaping from Neckbiter and his brainwashed followers. They must get help for the sabertooths before Neckbiter turns them into murderers and pariahs throughout Dinotopia.

Although Vornholt offers a weak excuse as to why mammals just happened to be offstage in all the previous books, the unavoidable implication is that ‘dinosaurs’ = ‘extinct animals’, so an extinct giant sloth is as much a dinosaur as is a stegosaur. Dinotopia theoretically separated from the rest of Earth’s land mass 50 or 35 million years ago, so the dinosaurs were spared from the evolutionary extinction which befell them elsewhere. Then early humans migrated to Dinotopia maybe 5,000 years ago, and the two have created a joint civilization since then. But for Dinotopia to also be populated with the Ice Age mammals, it would have to have remained connected to the other continents until only about 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. That’s an awfully short time for tectonic drift to have zipped it over the horizon and far away.

Nobody knows how smart dinosaurs really were, so it’s at least arguable that they could have been intelligent enough to understand the advantages of a civilization and to develop their own speech. But you can’t extend that intelligence to as recently as the dire wolves, prehistoric camels, and other Ice Age mammals without raising the question of when and why this intelligence abruptly disappeared, since today’s elephants, lions, or horses no longer have it.

The dramatic conflict in the other novels has already made it hard to accept Dinotopia as so harmonious that it never needs even civil arbitrators to mediate peaceful disagreements or misunderstandings. The literally backstabbing politics among the sabertooths here, and the panicked ‘kill the carnivores before they kill us’ mobs in a nearby human village, completely undermines this crucial plausibility.

The snowy avalanche that seals off the sabertooths’ valley is seemingly the first time such a disaster has ever occurred. Yet from the description of the narrow mountain pass, how could such an avalanche fail to happen every winter; or at least every twenty years or so? Alan Dean Foster, to his credit, shows in Dinotopia Lost that there are records and emergency plans to deal with disasters that may happen only once in hundreds of years. Vornholt in Dinotopia: Sabertooth Mountain gives the impression that Dinotopia is such a happy land that nobody has ever stubbed their toe in the past, so everyone is completely amazed and unprepared when the slightest inconvenience happens. It is totally unconvincing.

Hmmmph. On the one hand, I feel that I’ve hardly started on this review. On the other hand, I feel that I’ve already wasted more space on it than it deserves. Let’s hope that Dinotopia: Sabertooth Mountain is just a bad book, and not so abysmal that it ridicules the whole concept of Dinotopia into oblivion. ![]()

|

|